Saudi Arabia’s quest for strategic autonomy (GS Paper 2, International Relation)

Context:

- The Saudi Arabia’s drive to autonomise its foreign policy and build regional stability through diplomacy and its serious implications for West Asia.

How is Saudi foreign policy changing?

Saudi-Iran rapprochement:

- For years, the main driver of Saudi foreign policy was the kingdom’s hostility towards Iran. This has resulted in proxy conflicts across the region.

- For example, in Syria, Iran’s only state ally in West Asia, Saudi Arabia joined hands with its Gulf allies as well as Turkey and the West to bankroll and arm the rebellion against President Bashar al Assad.

- In Yemen, whose capital Sana’a was captured by the Iran-backed Shia Houthi rebels in 2014, the Saudis started a bombing campaign in March 2015, which hasn’t formally come to an end yet.

- One of the demands the Saudis made to Qatar when it imposed a blockade on its smaller neighbour in 2017 was to sever ties with Iran. However, the Qatar blockade came to an unsuccessful end in 2021.

New diplomacy:

- In March 2023 Saudi Arabia announced a deal, after China-mediated talks, to normalise diplomatic ties with Iran.

- Soon after, there were reports that Russia was mediating talks between Saudi Arabia and Syria, which could lead to the latter re-entering the Arab League before its next summit, scheduled for May in Saudi Arabia.

- Recently, a Saudi-Omani delegation travelled to Yemen to hold talks with the Houthi rebels for a permanent ceasefire.

- All these moves mark a decisive shift from the policy adopted by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman after he rose to the top echelons of the Kingdom in 2017.

- This is happening at a time when Saudi Arabia is also trying to balance between the U.S., its largest arms supplier, Russia, its OPEC-Plus partner, and China, the new superpower in the region.

Why are there changes now?

- The Saudi Arabia’s response to the Iran problem has shifted from strategic rivalry and proxy conflicts to tactical de-escalation and mutual coexistence. A host of factors seem to have influenced this shift.

- In Syria, Mr. Assad, backed by Russia and Iran, has won the civil war.

- In Yemen, while the Saudi intervention may have helped prevent the Houthis from expanding their reach beyond Sana’a and the north, the Saudi-led coalition, which itself is now in a fractured state, failed to oust them from the capital. Also, the Houthis, with their drones and short-range missiles, now pose a serious security threat to Saudi Arabia.

- In parallel, the U.S.’s priority is shifting away from West Asia. So the choices Saudi Arabia is faced with, is to either double down on its failed bets seeking to contain Iran in a region which is no longer a priority for the U.S., the kingdom’s most important security partner, or undo the failed policies and reach out to Iran to establish a new balance between the two.

Is Saudi Arabia moving away from the U.S.?

- It is not. The U.S., which has thousands of troops and military assets in the Gulf, including its Fifth Fleet, would continue to play a major security role in the region.

- For Saudi Arabia, the U.S. remains its largest defence supplier. The Kingdom is also trying to develop advanced missile and drone capabilities to counter Iran’s edge in these areas with help from the U.S. and others.

- But at the same time, the Saudis realise that the U.S.’s deprioritisation of West Asia is altering the post-War order of the region.

- What Saudi Arabia is trying to do is to use the vacuum created by the U.S. policy changes to autonomise its foreign policy.

What are the implications for the region?

- If Syria rejoins the Arab League, it would be an official declaration of victory by Mr. Assad in the civil war and would help improve the overall relationship between Damascus and other Arab capitals.

- Likewise, if the Saudis end the Yemen war through a settlement with the Houthis (which would probably split Yemen), Riyadh would get a calmer border while Tehran could retain its existing influence in the Saudi backyard. Such agreements may not radically alter the security dynamics of the region but could infuse some stability across the Gulf.

Challenges:

- While the Saudis are trying to build cross-Gulf stability, another part of West Asia remains tumultuous, which was evident in the Israeli raid at Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa, Islam’s third holiest place of worship.

- This triggered rocket attacks from Lebanon and Gaza and in return Israeli bombing of both territories. Israel also keeps bombing Syria with immunity. The impact of escalation of tensions between Israel and Iran on cross-Gulf stability remains to be seen.

US Factor:

- Another challenge before Saudi Arabia is to retain the course of autonomy without irking the U.S. beyond a point. Though the U.S. publicly welcomed the Saudi-Iran rapprochement, it complained about being “blindsided” on the Iran deal.

- The U.S. would also not be happy with Syria, where it once sought regime change, being re-accommodated into the West Asian mainstream.

- In post-War West Asia, the U.S. had been part of almost all major realignments; either through force or talks, from the Suez war to the Abraham Accords.

- But now, when China and Russia are mediating talks between rivals successfully and Saudi Arabia, a trusted ally, is busy building its own autonomy, the U.S., despite its huge military presence in the region, is reduced to being a spectator.

IMD forecasts a ‘normal’ monsoon, even as El Nino looms large

(GS Paper 1, Geography)

Why in news?

- India’s four-year run of munificent summer monsoon rainfall is likely to end in 2023, with the India Meteorological Department (IMD) forecasting a 4% shortfall in the coming monsoon season.

- Though still categorised as ‘normal’, it is at 96% of the Long Period Average (LPA). Most recently, it was in 2017 that the IMD forecast 96% in April, for the monsoon, and India saw a 2.6% shortfall.

Factor responsible:

‘El Nino’ effect:

- From 1951-2022, there have been 15 ‘El Nino’ years, defined as a greater-than-half-degree Celsius rise in temperatures in the central, equatorial Pacific Ocean with nine of those years witnessing ‘below normal’ rains. In 2015, the last ‘strong’ El Nino year (>1.5 C rise), monsoon rains shrivel by 14%. A ‘weaker’ El Nino (a sub-1C rise) in 2018 saw a contraction of 7.4%.

- Experts say that while ‘El Nino’ conditions are imminent, there are ameliorating factors that may blunt its impact. One, ‘El Nino’ is only likely to begin to take root in the second half of the monsoon season – August and September.

- The weather models also indicate the development of a ‘positive’ phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD, or warmer temperatures in the Arabian Sea and hence more moisture and rainfall over India) during these months and so, a somewhat reduced impact of the ‘El Nino’.

- Another factor that could blunt the ‘El Nino’ is reduced snow cover in Eurasia.

- In 1997, despite a ‘strong’ ‘El Nino’, monsoon rainfall turned out to be 2% more than normal and this was due to favourable IOD conditions.

Cultivation concerns:

- India’s kharif sowing, which begins in June, is extremely dependent on monsoon rainfall.

- In recent years, the IMD has started to place greater emphasis on the ‘dynamical’ monsoon forecast techniques where global atmospheric and ocean conditions are simulated on powerful supercomputers to forecast climate conditions.

- This is different from the traditional, statistical approach where 8-10 meteorological factors, such as Eurasian snow cover and Arabian Sea surface, are correlated to the monsoon rainfall in past years to forecast a coming year’s monsoon.

What is La Nina?

- La Nina is abnormal cooling of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean waters off the coasts of Ecuador and Peru.

- Such cooling (Sea surface temperature (SST) falling 0.5 degrees Celsius or more below a 30-year average for at least five successive three-month periods) is caused by strong trade winds flowing west along the Equator, taking warm water from South America towards Asia.

- The warming of the western equatorial Pacific causes enhanced evaporation and concentrated cloud-formation activity around that region, with consequences for India as well.

- The latest La Nina event lasted from July-September 2020 to December-February 2022–23, making it one of the longest ever.

El Nino:

- During El Nino, the trade winds diminish or even change direction, blowing from east (South America) to west (Indonesia). Warm water masses migrate into the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean as the winds blow from west to east.

- As a result of the rise in SSTs, rainfall increases in western Latin America, the Caribbean, and the US Gulf Coast, whereas convective currents are cut off in Southeast Asia, Australia, and India.

Long-Period Average (LPA)

- IMD uses the long-period average (LPA) to determine if the rainfall is normal, below normal, or above normal.

- The LPA, is the rainfall recorded over a particular region for a given interval (like a month or season) averaged over a long period like 30 years, 50 years, etc.

- Usually, in India, a 50-year LPA covers large variations on either side caused by years of unusually high or low rainfall due to El Nino or La Nina.

- India defines average, or normal rainfall as between 96 per cent and 104 per cent of a 50-year average with 88 centimetres (35 inches) of rainfall for the four-month season beginning June. IMD maintains LPAs for the entire country on a national and local level.

Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD):

- It is defined by the difference in sea surface temperature between two areas (or poles, hence a dipole) – a western pole in the Arabian Sea (western Indian Ocean) and an eastern pole in the eastern Indian Ocean south of Indonesia.

- The IOD affects the climate of Australia and other countries that surround the Indian Ocean basin, and is a significant contributor to rainfall variability in this region.

Vertebrates received genes for vision from bacteria, finds study

(GS Paper 3, Science and Tech)

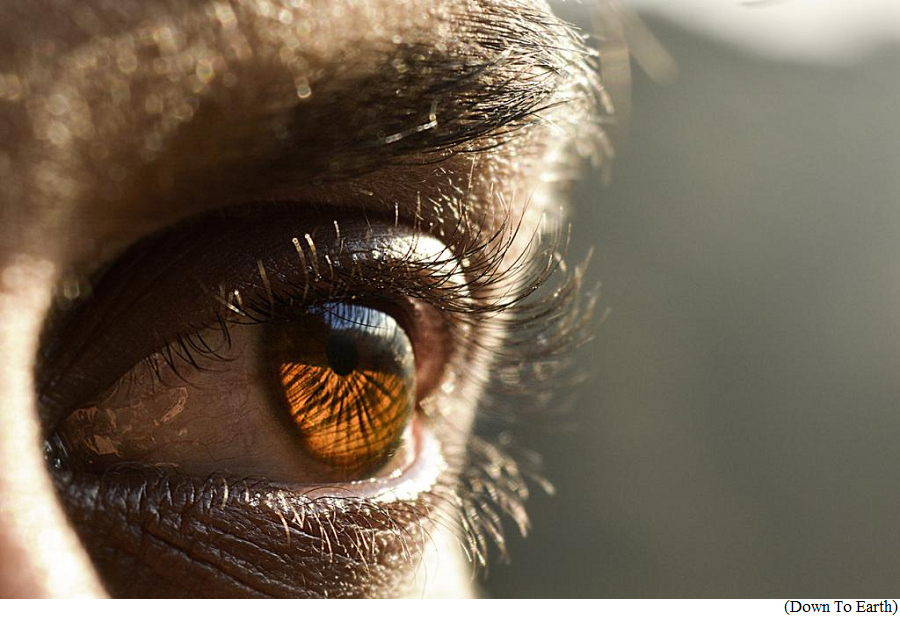

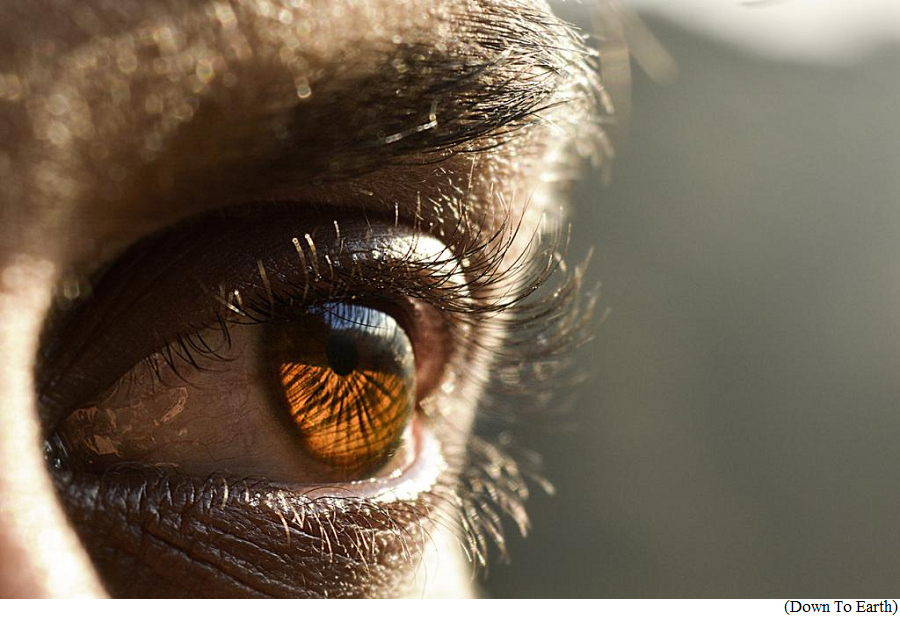

Why in news?

- A key gene involved in vertebrate vision has been traced back to bacteria, according to a new study.

- Some 500 million years ago, the bacteria likely transferred the gene to the ancestor of all vertebrates.

IBRP:

- The gene with links to bacteria contained instructions to make the interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IBRP).

- Its protein sequence is most similar to a bacterial protein called peptidases, which are known to break down proteins and recycle them.

- IBRP has a key role in vision. In humans, mutated versions of the gene lead to various retinal diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa (an eye disorder that causes loss of sight) and retinal dystrophy (a degenerative disorder that causes colour blindness or night blindness and complete blindness in progressive conditions).

Background:

- Scientists did not have a complete picture of how vertebrate vision evolved. This is because advances in eye arrangements occurred in animals that lived about 500 million years ago.

- Consequently, these animals were either not preserved or were not represented in the fossil record.

- Further, animals possessing intermediate eye features likely perished due to competition with their counterparts having better visual features.

- Researchers from the University of California, San Diego, tried to connect the missing dots by reconstructing the origin of IBRP.

Basics of research:

- They performed a phylogenetic reconstruction, which describes evolutionary relationships in terms of the relative recency of common ancestry.

- They found “unequivocal evidence” that a vertebrate ancestor acquired the bacterial gene. It duplicated itself twice. Further mutations in the gene resulted in IBRP with a new function.

- The transfer likely occurred due to interdomain horizontal gene transfer, which describes the movement of genetic information between organisms.

- The analysis identified two additional independent instances of the transfer of bacterial peptidase genes into eukaryotes, once into fungi and once into amphioxus species, key marine animals in understanding the origin of vertebrates.

- The researchers, however, could not identify the bacteria that transferred its gene to vertebrates.

Significance:

- It reveals further evidence that bacterial genes provide a rich source of evolutionary novelty, not just to other bacterial species, but to eukaryotes (animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms) as well.